Fast Facts

Fast Facts

Learn more about how government officials caused the Flint water crisis and repeatedly failed the people of Flint.

Government officials caused the Flint Water Crisis with their decision to switch the water supply to the Flint River.

For years, Flint had been receiving its water from the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department (DWSD); however, Flint's Emergency Managers believed Detroit water was too expensive. In turn, they chose to join a plan to build a new pipeline from Lake Huron to Flint, which would be run by the Karegnondi Water Authority (KWA).

Under the plan, the KWA would provide Flint with untreated Lake Huron water, which meant that Flint would have to treat the KWA water before it could be distributed to people's homes. Flint had a water treatment plant; however, the plant had barely been used for decades, and was going to need significant upgrades to operate effectively. Additionally, upgrades would cost tens of millions of dollars, which the City of Flint did not have.

Ultimately, the City decided to take the money that they had been using to buy water from Detroit, and use that money instead to upgrade Flint's water treatment plant so it would be ready for the KWA plan; however, it would take years for Flint's water treatment plant to be ready for use.

In the meantime, the City needed to determine how they could provide residents with water, since the money used to purchase Detroit water was now going to treatment plant upgrades. Ultimately, the City of Flint decided to acquire their water from the Flint River. Shockingly, the City did this without properly testing the water first to ensure it would be safe for utilization or consumption.

The City of Flint switched water from Detroit water to the Flint River on April 25, 2014; however, immediately after the switch, residents began complaining that water coming from their faucets was brown and foul-smelling and also reported feeling sick after consuming it.

Nevertheless, for nearly a year and a half, the government officials that had the power and ability to fix this problem did nothing.

Governor Snyder did not order a return to Detroit water until October 2015 - nearly 18 months after the initial switch was made.

The Government refused - for nearly 18 months - to consider a return to the original water source even after the water quality issues were widely known in Flint.

The idea of returning to the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department (DWSD) - Flint's original water source - had been repeatedly rejected by City and State officials well before, during, and after VNA consultants worked under the City.

Officials described a return to DWSD water as "cost prohibitive." Simultaneously, staff in the Governor's office recognized internally that drinking Flint River water was "downright scary," yet even their efforts to convince local officials to switch back to DWSD were futile, given the "high costs of switching."

During VNA's engagement, City officials instructed VNA not to review the decision to switch to Flint River water and not to recommend switching back to Detroit water.

Notably, when the water quality issues in Flint became apparent, Susan McCormick, the former Director of the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department (DWSD), offered to reconnect the City of Flint to DWSD at no extra cost, which would have provided residents with reliable, safe, and high-quality drinking water immediately. Still, government officials rejected this offer even after being made fully aware of the high lead levels found in Flint.

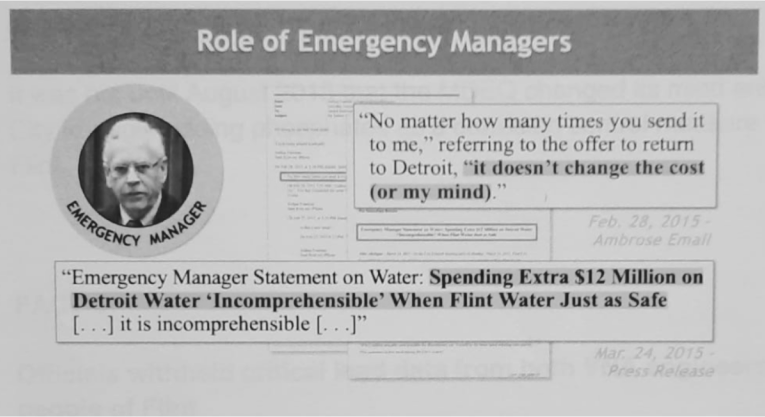

In February 2015, Emergency Manager Gerald Ambrose prevented the City from returning to Detroit water, even when the City risked running out of drinking water altogether.

Flint Water Treatment Plant staff started to prepare to return to purchasing water from the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department, in case the City's drinking water reserves reached depletion. Remarkably, Ambrose overruled those emergency preparations, telling the staff that a switch back to DWSD water "wasn't going to happen."

After the City Council voted to return to Detroit water on March 23, 2015, Ambrose overrode the vote and steadfastly refused to do so, calling the vote "incomprehensible."

Thousands of more residents became ill (some chronically) from the water before Governor Snyder ordered a return to Detroit water in October 2015 - nearly 18 months after the initial switch was made.

The Government failed to implement corrosion control to protect residents' water supply.

The Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) approved the City of Flint's plans to use the Flint River as an interim water source without requiring the use of corrosion control, despite being aware that the Flint River was contaminated and highly corrosive.

Stephen Busch, water supervisor for District 8 (Lansing) at the MDEQ from 2012 to 2016, gave the approval to Flint officials to move forward with the switch from DWSD to the Flint River without the use of corrosion control treatment.

Later, when Mr. Busch became aware of a pervasive lead problem in Flint, he still did not mandate corrosion control treatment and even advised against VNA's recommendation to do so, citing the Flint River as a temporary water source and that corrosion control would take too long to implement.

Later, Miguel Del Toral, a long-time employee of the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), testified that the Flint Water Crisis was caused by several factors, including the decision to switch to the more corrosive Flint River as a water supply, the presence of lead service lines in the distribution system, and, most importantly, the City's failure to practice corrosion control.

Additionally, Mr. Del Toral stated that when he asked Mr. Busch of the MDEQ directly about corrosion control, Mr. Busch responded that Flint had an optimized corrosion control program even though he knew this was a lie.

It was not until August 2015 that the MDEQ changed its mind and directed the City to begin adding phosphates as a corrosion control measure to the water in Flint.

Officials withheld critical lead data from both VNA engineers and the people of Flint.

VNA consultants requested all available lead and copper testing results from the City; however, the information that was provided showed the water to be in compliance with state and federal standards. VNA's engineers had no reason to suspect the City provided faulty lead testing data to them.

Flint Mayor Dayne Walling, Emergency Manager Gerald Ambrose and officials from the MDEQ and EPA all knew of the high lead levels in Flint resident LeeAnne Walters' tap water but did not inform VNA consultants or the public, despite VNA consultants' request that the City provide them with all relevant lead sampling data.

Astonishingly, the City of Flint altered data in their final report to the MDEQ and EPA in order to maintain compliance with Lead and Copper regulations.

Former Flint Water Treatment Operator Michael Glasgow testified that Ms. Walters' high test result of 104 ppb prompted the EPA to ask the MDEQ for the City's Lead and Copper rule report.

The MDEQ's Michael Prysby and Steven Busch instructed Mr. Glasgow to lower the required number of samples from 100 to 60 and remove the two high test results from the report, including the one from Ms. Walters' home, in order to show compliance with the Lead and Copper testing rule.

The Flint Water Crisis was "an infamous government-created environmental disaster".

The Flint Water Crisis was a massive failure of government, from the politicians at the very top of state government, including Governor Snyder himself and members of his senior staff, to the bureaucrats on the ground in Flint.

The Governor's Task Force Report issued on March 21, 2016, found that: "The Flint water crisis is a story of government failure, intransigence, unpreparedness, delay, inaction, and environmental injustice. The Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) failed in its fundamental responsibility to effectively enforce drinking water regulations."

On July 19, 2018, the EPA Office of Inspector General Report similarly found that

"[t]he circumstances and response to Flint's drinking water contamination involved implementation and oversight lapses at the EPA, the state of Michigan, the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ), and the city of Flint."

The Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals has referred to the Flint Water Crisis as an "infamous government-created environmental disaster."

On January 14, 2021, Michigan Solicitor General Fadwa Hammoud and Wayne County Prosecutor Kym L. Worthy announced the indictment of nine individuals on a total of 42 counts related to a series of alleged actions and inactions that allegedly created the historic injustice of the Flint Water Crisis.

In announcing the indictments, Solicitor General Hammoud stated that the Flint Water Crisis was the result of a "categorical failure of public officials at all levels of government, who trampled upon their trust, and evaded accountability for far too long." Charges against all nine of these individuals were dismissed by the Genesee County Circuit Court due to procedural defects in the prosecution's indictment process.

Veolia had no responsibility or permission from the government to treat Flint Water.

The responsibility for the Flint Water Crisis rests with the public officials who decided to switch the City's water supply to the Flint River at the expense of the health of Flint residents.

The Flint Water Treatment Plant was run by the City, not VNA consultants. VNA's consultants were never tasked with operating the Flint Water Treatment Plant. At no time did VNA consultants have any power or authority to direct, or insist upon, any changes to how Flint residents received their water, and consultants were never authorized to test water in people's homes.

VNA consultants were hired ten months into the crisis - when the City of Flint had already switched its water source from treated Lake Huron water to untreated Flint River water. Their scope was to conduct a one-week review of the operations of the Flint Water Treatment Plant and provide recommendations to the City of Flint on how to help solve the significant problems caused by a cancer-causing chemical in the water called Trihalomethane (TTHM) and how to improve the City's water quality.

These recommendations included operational changes, differences in water treatment regimens and chemical dosing, increased maintenance and increased training.

In their final report to the City, VNA consultants urged Flint officials to work with the City's engineer and the MDEQ to evaluate the need for corrosion control and the use of phosphate for that purpose. The City of Flint never implemented that suggestion.